Source: International Labour Organization, 2020. Note: Data reflects % of female and % of male populations age 15+. Data includes Albania, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Russia, Serbia, Tajikistan, Turkey, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, and Uzbekistan.

Source: ILOSTAT, 2019.

Note: In Europe and Central Asia the gender pay gap ranges from 7 % in Kazakhstan to 44 % in Belarus. Data is not available for Albania, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. The gender pay gap is unadjusted and is calculated as the difference between men's and women's average monthly earnings as a percentage of men's average monthly earnings.

Source: EU4Digital, 2018

Note: Data available only for Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine

Can you identify the many barriers women face when trying to get a job in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM)? We must spread awareness and understanding of the norms and systemic gender bias that keep women from advancing in STEM careers, so that we can create effective strategies to meet the demands of the future of work Europe, Asia, and the Pacific.

Bias in job descriptions and hiring processes

The way a job description is written could influence women applicants. Using terms like manpower, fearless and ambitious are known to appeal to men more than women. Gender-sensitive, inclusive language can help attract more women.

Exclusionary work cultures

Being the only woman in the workplace can be intimidating. A lack of diversity and inclusion strategies creates isolating, unwelcoming workplace environments for women, affecting job satisfaction, retention and opportunities for upward mobility. Without the social capital (such as mentors and networks) necessary for advancement in their careers, women tend to leave their jobs. Those who stay often find their progress stalled, while men advance to managerial and decision-making positions.

Gender pay gap

Women face both gender pay gaps and glass ceilings in the private sector even when they possess similar skills and experience. Leadership positions also influence the size of the pay gap: not only are there fewer women at the top, but that is where the differences in earnings are the largest. Being transparent about salary and equity ranges with defined performance measurables may help to create a level playing field and reduce the gender pay gap.

Women are typically given smaller research grants than their male colleagues and, while they represent 33.3% of all researchers, only 12% of members of national science academies are women globally.

Source: United Nations 2022

Non-standard forms of employment, such as part-time, temporary or zero-hour contracts, casual/gig work and crowd work on digital platforms is more widespread across STEM sectors and occupations than in traditional sectors. On-line platforms are becoming a key channel for brokering labour supply and demand connecting STEM professionals with clients. Although gig work offers benefits such as flexible hours, ability to work from home, including in international projects, evidence suggests that gig STEM jobs are not immune to gender imbalances. Women tend to accept shorter contracted hours and lower per-hour payment than men.

Freelancing during the COVID-19 pandemic

COVID-19 measures such as online learning and closing childcare centers, have shifted more care work to women, forcing them to extend themselves to balance responsibilities or reduce or leave paid work, with little to no social protection in the event of changes in the duration of contracts or non-extensions. In parallel, the COVID-19 pandemic and the social distancing measures adopted by governments have accelerated a trend toward distant work, potentially leading to further globalization of projects and possibilities for offshore freelancers in STEM, especially in ICT. When properly remunerated, freelancing and blended work regimes may createmore inclusive working environments for women as well as for men to balance work with household responsibilities and create more equal distribution of care work, including childcare.

Freelance and gig work as a challenge

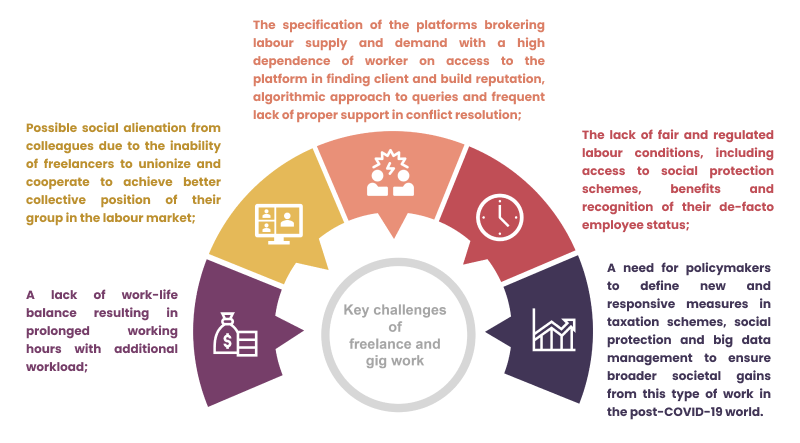

Despite creating new opportunities, the platform economy poses challenges that need to be addressed by policymakers and social actors such as trade unions and worker’s coalitions. The greater the flexibility and the more individualistic the nature of the work, the more vulnerable, paradoxically, the gig worker’s position. Some of the key challenges related to freelance/platform work are:

A noteworthy phenomenon is the rise of new forms of e-collaboration and e-cooperation among freelancers and gig workers. Platform cooperatives which use business models similar to better-known apps or websites allow cooperative ownership of computing platforms, offering its users, including workers, better negotiating positions, recognition of their digital labour, and democratic control over resources.

Sign up to receive STEM4ALL updates and news as we continue to grow and expand.